Downtown generates far more property tax revenue than big box stores, analysis shows

Findings come as city struggles to afford to fix deteriorating roads and other infrastructure

Despite moving away from Peterborough a few times, Andrew McMullan kept getting pulled back to the hometown he loves. “It’s like a vortex,” he said.

Back in Peterborough these days, McMullan is once again a regular at the downtown corner store that was a fixture of his childhood – Jerry’s Quik Chek.

“Jerry’s Quik Chek is… a staple of Peterborough. It’s been here for so many years,” said McMullan.

Humble little shops like this one – in dense, walkable neighbourhoods – deliver a surprising amount of financial value for Peterborough, according to a recent economic analysis of the city’s development patterns. The analysis, conducted by the North Carolina-based firm Urban3, looked at the property tax value of land per hectare citywide.

Jerry’s Quik Chek, on the corner of Park and Sherbrooke streets, generates $133,000 in property tax per hectare, significantly more than what the city gets from big box stores, according to the analysis.

Peterborough’s two Walmart stores on average deliver only $74,000 in property taxes per hectare, while Costco brings in $47,000 per hectare.

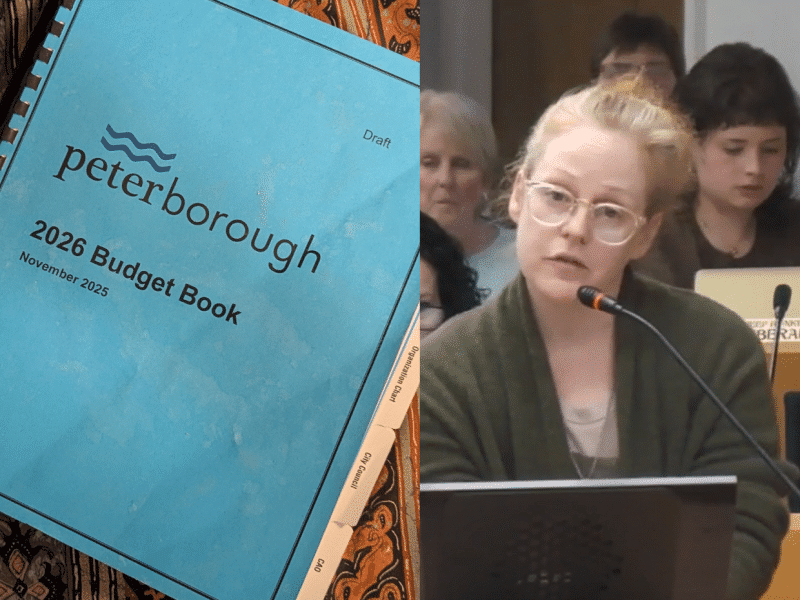

The findings were presented at a public event the city held at the Market Hall on May 28. They show which areas of Peterborough are contributing the most in property taxes, as staff warn that the city is struggling to afford to maintain deteriorating roads and other infrastructure.

The analysis shows how Peterborough could raise more money to pay for infrastructure and other priorities if it develops more densely.

“You’re actually not using a lot of your land efficiently,” said Joe Minicozzi, an urban designer and founder of Urban3, as he presented the findings at the event.

The oldest part of the city is one exception to that, according to Minicozzi. Downtown generates 13 percent of Peterborough’s property tax revenue, even though it only occupies five percent of the city’s land area.

Many of the 19th and early 20th century buildings in the core bring in $200,000 to $1 million in property tax revenue per hectare, the analysis revealed. “Your [great] grandparents had horse technology and dirt roads – and they left you these gems,” said Minicozzi, referring to some of the historic buildings that line George Street.

312 George Street, a 1915 art deco building that is currently home to Peterborough Inn and Suites, brings in $604,000 per hectare in property tax. “Go give that building a hug, it’s giving ya big value,” he said.

Historic downtown buildings have a number of features that raise their property values. Most have offices or apartments stacked above their main-floor retail space, they come with little or no on-site parking, and they were built to last for generations.

But big box stores occupy large tracts of land, much of which is taken up by parking, thereby lowering their property values and resulting in less tax money for the city.

“When you actually add more parking, you’re essentially diluting the value,” Minicozzi said. He said that while parking at big box stores may seem free, residents pay for it in the form of less tax revenue to run the city.

Like many North American cities, Peterborough has sprawled out considerably since the 1960s, but that hasn’t created more wealth for the community, according to Minicozzi.

“This land is sacred. It’s a sacred gift that’s been given to us,” he said. “Why would you waste it?”

Another finding is that apartment buildings provide vastly more property tax revenue than single family homes.

Single family homes generate less than $60,000 in property taxes per hectare on average, whereas apartment buildings bring in $179,000 per hectare on average, Minicozzi said.

The event came a few days before the city released an update to its asset management plan, which shows that Peterborough faces an approximately $135 million annual infrastructure deficit. The infrastructure deficit is, basically, the amount of money the city lacks each year to maintain existing roads and other infrastructure and build more to accommodate growth.

According to the report, 84 percent of Peterborough’s community housing facilities are in poor condition, 28 percent of Peterborough roads are in poor or very poor condition, and 14 percent of transit buses are past their useful life and need to be replaced.

Peterborough also has big gaps in its sidewalk network, including at many transit stops. But progress to build the 361 kilometres of missing sidewalks has been slow. Last year only one kilometre – or 0.3 percent – of missing sidewalks was installed, according to the report.

“Public infrastructure is often looked at as the backbone of our economy and quality of life,” the report states. “Unfortunately, years of under investment throughout the country has resulted in years of deferred repairs.”

“Canada is beginning to confront its ‘infrastructure deficit’ but it is not without challenges. Peterborough and most other municipalities struggle with the same infrastructure challenges.”

The state of Peterborough’s roads is “ridiculous,” according to McMullan, the Jerry’s Quik Chek shopper.

“I’ve lost at least six tires in the last two years because of the potholes that are unavoidable,” he said. “To see the money go into where it needs to go would be incredible.”

The consequences of the infrastructure shortfall can be seen in the state of downtown streets, which are getting so bad that city staff warned last year that they risk falling into an “unmanageable state of repair.”

City council agreed to spend $2.3 million this year to repave some downtown streets, including George and Water, as a temporary measure. But they will need to be torn up again when funding is available, to replace underground infrastructure that is also deteriorating, according to budget documents.