Peterborough’s police budget has grown almost 50 per cent in four years. Does that make sense?

What goes into a police budget? And is it the best way to improve public safety?

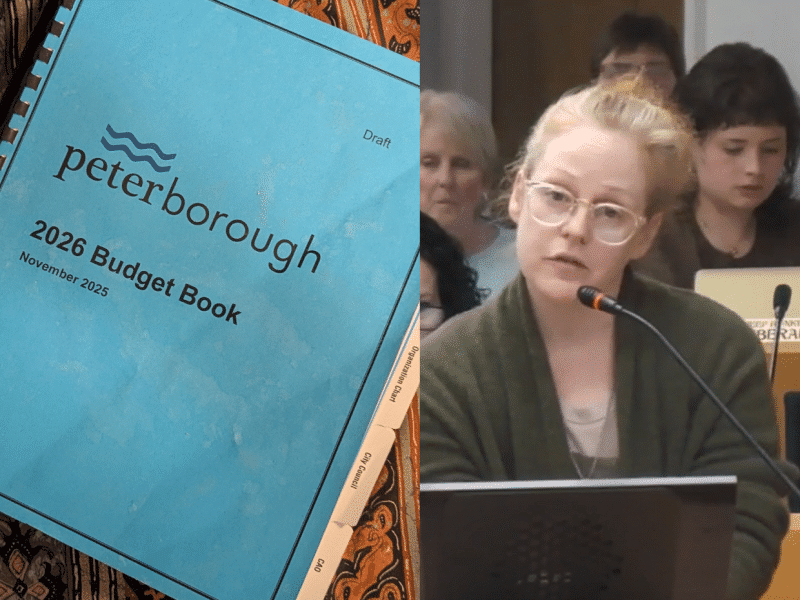

As part of this year’s budget proceedings, Peterborough Police Chief Stuart Betts and the Peterborough Police Services Board are requesting a 9.22 per cent increase to the city’s contribution to their operating budget. This represents almost $3.5 million dollars more than last year and continues a period of rapid expansion for the city’s police budget. If the budget passes as written, Peterborough will have added over $13 million to the police’s budget since 2022, a 48 per cent increase in just four years, with no sign of slowing down.

These increases are significant for the citizens of Peterborough. The police budget represents roughly one-fifth of the city’s total tax spending, and this period of growing police budgets has also seen significant increases to Peterborough’s property tax rate. The police budget is also profoundly complex, representing a large organization responding to pressures from citizens and all levels of government, constrained by complex legal strictures, and operating under uncertain assumptions about public safety and how best to maintain it.

What is causing these increases to the police budget? How does a city determine what’s reasonable for a police budget? Are these increases making us safer? And, in a time of increased awareness of the problems of policing, particularly around marginalized communities, are there alternate options we could be funding to keep people safe?

A history of police budget increases

When Stuart Betts became Peterborough’s police chief in 2023, he arrived into nearly a decade of almost flat increases to the police budget, all falling in the range of 2 to 3 per cent, roughly accounting for rising inflation and nothing beyond. Chief Betts has referred to this as “essentially shrinkage,” saying it failed to keep up with mandated raises and benefits that are built into the force’s collective bargaining agreement, or the continued growth and evolving needs of Peterborough’s population.

“I recognize that we are entering a very challenging time fiscally,” he stated at the time, “but modernization comes with a cost.”

Arriving on the job in January 2023, nearly at the end of the municipal budget process, Chief Betts said he “inherited” the 2023 police budget, which included a 4.0 per cent increase. This was still the largest increase the police had seen in years, but it was dwarfed the following year, when the police requested (and received) an additional $4.75 million, a 15.3 per cent increase.

These increase requests have not been without controversy. For the 2025 budget, city council rejected the police’s original ask for an 8.8 percent increase, forcing them to return with a 7.7 per cent increase instead. “I don’t have a wish list. I have a necessity list and what I’m asking for is what has been asked for from this city since 2011,” said Chief Betts to council at the time. “This has far surpassed a wish list.”

For 2026, Mayor Jeff Leal used his strong-mayor powers to recommend the police board submit a budget including a 10 per cent increase. The board returned with a 9.2 per cent request. This represents an almost $3.5 million increase over last year and is currently under discussion as part of the municipal budget process.

(The increase for 2026 was originally reported at 9.8 per cent or $3.7 million but, as of the November 10 city council meeting, it’s been recalculated due to updated numbers related to employee benefits.)

This period of expanding budgets has also coincided with the ongoing project to renovate the aging Peterborough police station on Water Street and expand into a second administrative facility on Lansdowne Street West. Originally approved by city council last year at $66.5 million, this project ballooned to $91.9 million following a closed-door council meeting this past September. These funds are being paid out across the 2025, 2026, and 2027 municipal budgets.

Because this project is a special, one-time capital expense, it falls outside the scope of this article, which is focused on annual operating budgets. However, the police station project has added additional financial pressures onto the city and has led to a particularly heated tone of conversation around police budgets this year, with frequent mentions by members of the public during discussions of the police budget.

What’s in a budget?

As with most organizations, the vast majority of the Peterborough Police Service’s operating budget (almost 90 per cent) goes to staffing. The collective agreement reached in between the Peterborough Police Association and the police board in March 2024 dictates that a first-class constable in Peterborough will make $116,015 in 2025 and can expect raises between 2.5 and 4 per cent each year, until at least the end of the agreement in 2028.

Apart from retirements and layoffs, this creates a predictable and constant upward pressure on the police budget each year.

The next largest portion of the new budget request, as set out by Chief Betts, are new initiatives required by the provincial government. Ontario’s Community Safety and Policing Act (CSPA) came into effect in 2024 and is the first major overhaul of Ontario policing legislation in over three decades. It mandates sweeping changes across police services, including modernizing the process for suspending officers without pay, new board requirements, and – importantly for the budget – significant new requirements for training, certification, reporting, and oversight.

“That is the biggest and newest pressure,” says Chief Betts, “last year, this year, and quite frankly, into the coming years,” with some of the training required to be completed annually or biannually. There are also startup costs: “Some of the things that we have to provide, we simply don’t have the infrastructure in place to do.”

At the city council meeting on November 3, Councillor Matt Crowley presented a motion to council, written with Chief Betts’ assistance and passed unanimously, to “request that the Province of Ontario provide targeted financial assistance to municipalities” to help cover the costs associated with these new provincial requirements, and not require “general increases to police budgets.”

According to Councillor Crowley, there has as of yet been no response from the provincial government.

The final component emphasized by Chief Betts is new technological infrastructure. The police, who have significant technology needs beyond what the city generally provides, is bringing their IT services in-house and is also working to improve cybersecurity to protect against outside attacks.

Does more money for police lead to safer cities?

In public comments, Chief Betts often draws a direct parallel between police budgets and public safety. During the police budget information presentation this past October, he referred to the large budget in 2024 as “the first big investment in public safety in this city in over a decade,” and later said, “There’s a direct link between the budget and what we can provide.”

Chief Betts has a range of statistics to back this up: “We look at crime rates locally, at how many we are arresting, and are we clearing those calls?” Indeed, there is a well-established relationship here, and a logical one: more police on the streets can complete more arrests. Chief Betts points to rises in arrests and charges over the past several years.

What’s less clear is whether there’s a more general association between rising police budgets and an overall reduction in crime or increase in community safety. One major study published in 2023 looked at the police budgets of 20 major Canadian municipalities across 20 years, and compared them to the Crime Severity Index, or CSI, a crime statistic that factors in both the overall crime rate and the severity of the crimes. The study found no significant association between police budgets and this measure of public safety.

Running the equivalent numbers in Peterborough, up to 2024, the most recent year for which CSI statistics are available, yields the following:

As in the study, it shows no clear association between the two numbers, with significant variance in the CSI across years when budget increases were stagnant and little change in the years when the police received a major budget increase.

Melanie Seabrook, a co-author of the study, notes that, while budgets and CSI are “the two factors that we decided to compare to get an overall picture,” they don’t tell the whole story. “There is this lack of research in the area, but we need to be looking at all sorts of other control factors in future research,” including city demographics and what other, non-police crime prevention measures are in place.

Chief Betts also urges caution: “It’s a difficult one to say, because of the unpredictability of policing.” He notes that CSI, being a measure of crime severity, is weighted towards incidents of violent crime. Property crime receives less importance, even though it’s “often the bulk of what happens in a policing jurisdiction, and it directly impacts probably many more people.”

He also notes that there are other, more practical factors that he uses in evaluating the success of a police force, apart from public safety impacts. These include comparisons with goals set out in the police’s strategic plan, staff workload and productivity, and officer absenteeism due to work-related medical conditions, such as PTSD.

Ted Rutland, associate professor at Concordia University, presents an alternate view of the impact of police on public safety. He’s written extensively about the trajectory of Canadian police budgets, particularly since 2020, when international conversations shifted to Black Lives Matter and the Defund the Police movement. This argued that police budgets should be reduced (or, in extreme cases, eliminated entirely), with funds redirected towards community and social services.

Rutland says the Defund movement “came out of a recognition of two things. One is that the police obviously cause a lot of harm to Black people, Indigenous people, poor people, queer people, etc. And second, that there are other ways of keeping each other safe.”

Zero police forces across Canada actually reduced their budgets in response to this movement, though some cities had only “marginal” increases the next year, according to Rutland. However, since 2022, “we’ve seen a major kind of right-wing backlash of various kinds across Canada,” which has “tried to link the social crises that we face to crime, and claiming that the solution is more police. And so, since 2022, we’ve seen large increases in police budgets” across the country.

He notes how much of the public conversation around policing and police budgets revolves, not around hard data, but around a perceived “feeling of unsafety,” the general sense that a community is getting more dangerous, regardless of what the numbers show. “Research shows that the biggest impact on people’s feelings of unsafety is how much the media is talking about crime,” says Rutland. “We could make people feel tremendously safer, like in the next few months, if we just stop hyping up particular kinds of crime.”

A ‘fourth response’ to crime

In Peterborough, Chief Betts says “crime in general is really only reflective of between 18 and 22 per cent of our workload, and the rest is non-criminal in nature.” This lines up with national statistics: across Canada, it’s estimated that 70 to 80 per cent of all calls for police services are for non-criminal issues, and there have been many stories of interactions between police and people with mental health issues that ended tragically.

Police services have taken steps in improving mental health training for officers. Peterborough’s police force includes the Mobile Crisis Intervention Team, two teams consisting of an officer and a mental health worker, and legislation like the CSPA has mandated mental health training, but this remains an imperfect solution. Chief Betts himself has noted the strain on resources that it takes to pull active-duty officers off the streets for additional training.

One way that several cities did respond to the calls of the 2020 Defund movement was to establish a so-called ‘fourth response’ to 911 calls, besides police, firefighters, and ambulance. Rutland and Seabrook both highlight the work of the Toronto Community Crisis Service, an alternate emergency response team staffed by mental health professionals, who have had significant success providing assistance to people experiencing mental illness, substance use, and unhoused people, without the need to involve police or tie up their expensive resources.

Something similar was attempted in Peterborough, though without city funding. In 2024, a group of downtown business owners partnered with One City Peterborough and other community funders to create the Unity Project. Downtown businesses could call this new outreach team to come and assist with community members in distress, without involving the police.

The project only had a one-year funding commitment and closed at the end of the year, but its time included 305 calls for support and served as a new method for community engagement and support.

There is also a need for responses before a crisis point is reached. Seabrook is a researcher at the Upstream Lab, a non-profit research lab based at St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto, Ontario. There she studies “upstream solutions” that focus on prevention rather than reaction, stopping the path towards criminality before it happens.

Health and mental health services, long-term care, and social assistance all “help ensure that people are supported in living their healthiest lives and are able to thrive in the community,” says Seabrook, and improved child welfare services can ensure “that children are growing up in a safe and engaging environment, which has been linked to lower rates of criminal engagement downstream.”

Housing is also a major factor in this. In Peterborough, the United Way’s 2024 Point in Time report found that 82 per cent of unhoused people surveyed had a substance use condition, 72 per cent had a mental health condition, and almost half had a physical illness or disability, all of which increase reliance on emergency services and often result in interactions with the police. As one report co-authored by Seabrook notes, “Police cannot address [unhoused people’s] needs if they cannot be referred to housing support.”

However, Seabrook notes, “we’ve seen a de-prioritization of these types of services in terms of funding over the past 10 to 20 years, and so that’s led to all of these crises and social challenges that we’re seeing right now.”

Chief Betts agrees, at least in principle: “I wholeheartedly support having the right people respond to those types of calls. It’s not always a police officer, and I don’t think you’ll find a police chief who would say otherwise.”

However, he says, “you can’t simply flip a switch.” He notes that social services and emergency services also sometimes call on the police for enhanced security when dealing with difficult situations and “until the infrastructure is in place to be able to offload that work to another social service agency, you’re still going to have the police.” Any change would require a “transition time,” which would require significant funding put into both, as well as a more significant structural reorganizing of response services and budgets, at all three levels of government.

“I think it helps people pause,” says Seabrook, “and think a little bit more in depth: if investing in police isn’t necessarily reducing crime rates, what else do we need to do?”