Alderville First Nation grants legal personhood to Rice Lake

Exploring an alternate solution to climate change, and a growing international movement

In a resolution passed by Alderville First Nation’s band council, Rice Lake has been granted legal personhood status. This move asserts the lake’s right to exist, to flow, and even to sue would-be polluters, and sets up a Guardians Council to speak on its behalf.

This is a first in Ontario, but ecological personhood is a growing international movement. Led primarily by Indigenous groups, it’s an alternate response to ecological devastation and climate change. With a foundation rooted Indigenous ways of seeing the world, in biological science, and also in western legal practice, ecological personhood shores up essential protections for these natural features and helps them to continue sustaining ecosystems and human life.

A family member in distress

“Rice Lake is our past, our present and our future,” says Chief Taynar Simpson of Alderville First Nation. The lake, and the water systems across southern Ontario, have sustained the Mississauga Anishinaabe people for 10,000 years. “We’ve always seen the lake as a mother, a provider, in a way, as a family member.”

In addition to the manoomin (wild rice) that gives the lake its name and serves as a staple crop for the Mississauga people, Pemadeshkodeyong (Rice Lake) has historically provided the people of Alderville with pickerel and muskie to fish, and beaver, muskrat, and waterfowl to hunt.

But 200 years of western development have significantly harmed the lake. The damming and construction of the Trent-Severn Waterway flooded the area and destroyed Rice Lake’s yearly ebb and flow. The lake, located in the midst of cottage country and within a couple hours from Toronto, has also experienced overfishing and overhunting, and invasive species like pike and Asian carp have further impacted its biodiversity.

Multiple species who call the lake home have been identified as being under threat and in need of protection, including the black tern, the least bittern, the Blanding’s turtle, and the snake-necked turtle.

There are also pollutants. According to Craig Onafrychuk of the Baxter Creek Watershed Alliance, this includes both “legacy contamination,” left over from historical industrial dumping in upstream cities like Peterborough, and also ongoing polluting. Runoff from urban developments and industrial farming in the area, as well as illegal dumping, inhibit the growth of the rice beds that would be the habitat for fish and waterfowl, resulting in ripple effects across the ecosystem.

“And then,” says Graham Whitelaw, also of Baxter Creek, “you throw in the influence of climate change, everything from temperature change to weather. It’s a very complex situation.”

“Rice Lake used to be considered the number one fishing lake in all of Ontario,” says Chief Simpson, “but there’s no way it’s got that designation right now. We actually limit the number of fish we recommend you eat from the lake, because of the pollutants.”

There are laws against dumping and overfishing, but Chief Simpson says they aren’t being enforced, “because the lake doesn’t have a voice.”

Building a coalition

On November 17, 2025, the Alderville First Nation band council passed a resolution establishing Rice Lake as an ecological person and enumerating nine rights for the lake:

- the right to live, exist, and thrive

- the right to respect for its natural cycles

- the right to evolve naturally, to be preserved, and to be protected

- the right to maintain its natural biodiversity

- the right to perform essential functions within its ecosystem

- the right to maintain its integrity

- the right to be free from pollution

- the right to regeneration and restoration

- the right to take legal action

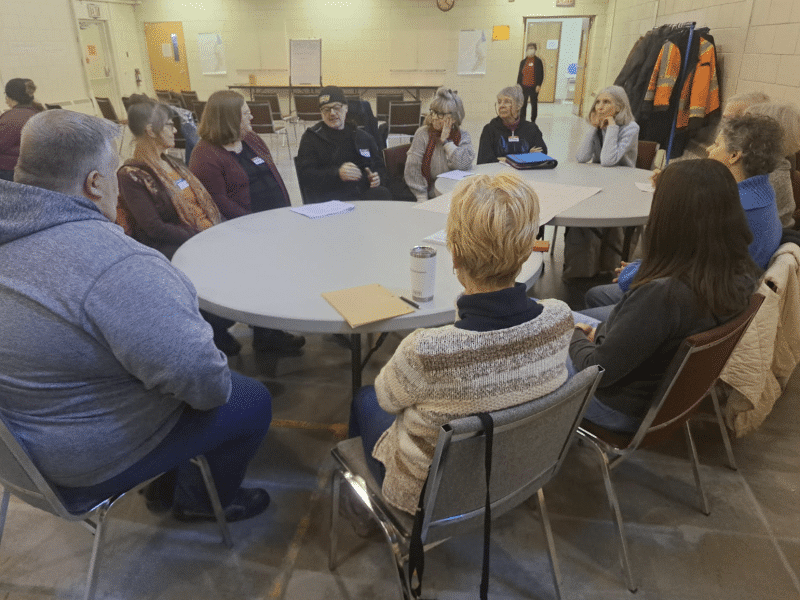

The resolution is the culmination of over two years of outreach and consultation, but this is only the beginning. Chief Simpson is currently building a Guardians Council of stakeholders, as outlined in the resolution, who will be able to direct the flow of action for the lake and speak on its behalf. This will include a remarkably broad spectrum of organizations, reflecting the complexity of the challenge they face, and the deep interconnections the lake has in the area.

Early on board were the other six Williams Treaty First Nations, including Alderville’s sister nation, Hiawatha, who are located on the opposite shore of the lake. Chief Simpson is currently on a whistlestop tour of the surrounding municipalities, meeting with mayors, councils, reeves, and community members, as well as representatives of the provincial and federal government. He says he’s received “soft support” from many, and is now looking to formalize that into concrete action.

Chief Simpson also contacted environmental lawyer Yenny Cardenas, of the International Observatory for the Rights of Nature, who had experience assisting the Innu people with Canada’s first-ever ecological person designation, the Magpie River in northern Quebec. “Each river or lake needs a different kind of help,” she says. “It’s like each person: sometimes our rights are violated for different reasons.”

Another ongoing partnership has been with the Millbrook-based Baxter Creek Watershed Alliance, a nongovernmental organization made up of scientists and experts in land use and environmental policy. The organization has conducted significant research and advocacy for Baxter Creek, including mapping and water quality testing, as well as outreach in the local community and schools.

“We care about the same things,” says Baxter Creek’s Onafrychuk. “We care about the health of our ecosystems, the health of our land and waters, for the benefit of people, now and for future generations.”

Baxter Creek winds its way through Millbrook, eventually exiting into the Otonabee River, passing through Peterborough, and then into Rice Lake, where good environmental data has been sorely lacking. Data will be essential in guiding future action by the Guardians Council. “If we think about human impacts to the ecosystem,” says Onafrychuk, “we can only really measure those impacts by understanding our baseline, then measuring from that.”

Chief Simpson also wants to bring local associations of homeowners and cottagers onto the Guardians Council, and even hunting and fishing organizations. “If you love the lake and you love enjoying the lake, this initiative is for you,” he says. “If you like fishing, then this is for you, because we’re trying to bring back the good fishing species.”

Can a lake be a person?

For those unfamiliar with ecological personhood, the concept is sometimes met with confusion or bemusement (or strong negativity, fuelled in part by a fearmongering article about the Alderville resolution that appeared in Rebel News). But the idea has a strong basis in Indigenous ways of seeing, in biology, and even in the Canadian legal system.

For the Anishinaabe, nibi (water) “is life,” says Chief Simpson. “Water is alive. We see everything as our relatives: animals, plants, mountains…. We are all connected. We’re all part of the same planet. We all share atoms and molecules in our body. Whether we like it or not, we’re all part of the same ecosystem. We’ve always seen water as life; this is just a way to formally recognize it.”

As cited in the Alderville resolution, the Anishinaabe principle of mino-bimaadiziwin (good life) teaches that “all beings are alive and sacred, and that humans have reciprocal obligations of care and respect toward the land, waters, and all of our more-than-human world.”

On a biological level, Rice Lake is unquestionably full of life, home to a thousand different species of microorganisms, plants, fish, mammals, birds, and amphibians. All of them interact in a dynamic and evolving way, and with the people who live on the lake or come to visit it. The lake changes, responding to the seasons and to what other living things add to it or remove from it.

Even within our legal system, extending personhood to non-humans is a well-established practice. In Canada and all other western countries, corporations are considered legal persons – not “natural persons,” as humans are described, but persons nonetheless. Cardenas describes personhood for corporations as “a fiction,” but a useful one, which allows corporations to “interact better with the legal framework, and have rights and responsibilities.” It means corporations can own property, enter into contracts, sue and be sued, all without the need for a ‘natural person’ to serve as an intermediary.

The United States Supreme Court has even affirmed corporations’ right to freedom of speech, in a controversial 2010 decision that eliminated limits on corporate donations to political campaigns, on the argument that money is speech and speech is protected by the constitution.

When so many of the threats to Rice Lake come from corporate persons, including property developers and industrial dumpers, “in a lot of ways, attributing legal personhood to the lake just lets them meet on the same level,” says Chief Simpson.

A growing international movement

Ecological personhood is a growing international movement, led in large part by Indigenous groups, as an alternate response to climate change, ecological devastation, and over-development. In 2008, Ecuador became the first country to enshrine the rights of nature in its constitution, and in 2017, the Māori people settled 140 years of negotiation with the New Zealand government by establishing a legal identity for the Whanganui River.

What started as a trickle has turned into a torrent of activism and legal decisions, with rights of nature movements reaching at least 44 countries, and personhood being established for the Ganges River in India, Taranaki Maunga mountain in New Zealand, the Amazon in Columbia, the Mar Menor lagoon in Spain, and even all of Mother Earth, thanks to legislation in Bolivia.

In Ecuador, the Los Cedros cloud forest has even seen its day in court. Facing extreme deforestation, a group took a state-owned mining company to court, arguing their actions violated the forest’s rights. To many people’s surprise, the court sided with the forest, and mining operations in Los Cedros have ceased entirely.

The Magpie River in northern Quebec became the first ecological person in Canada, thanks to the efforts of the Innu people to protect the river from increasing hydroelectric development in the area, and now Rice Lake becomes the first such case in Ontario.

Chief Simpson announced the Rice Lake resolution to the world in November 2025, as an invited guest at the United Nations’ COP30 climate change conference in Belém, Brazil. “People were very excited,” recalls Cardenas, who was also in attendance.

The theme of the conference was Mutirão, or collective action. This reflected the multifaceted response that will be required to combat climate change, a worldwide effort at all levels of government and society – but it also felt like an acknowledgement of institutional failures in the response to climate change thus far. The conference was a wellspring of community-led initiatives that sidestep the need for large governments and multinational corporations, and Indigenous groups were a major presence at the conference.

“It was the COP30 of the people,” says Cardenas. “Everyone had to do something, not wait for the federal government. We can do, as individuals, as Indigenous orders, as local communities. I myself can take a step for climate change and to protect water biodiversity.”