Young and old learn side by side in Trent’s “intergenerational classroom”

Course focuses on the psychology of aging, and older adults are present every week to share their knowledge

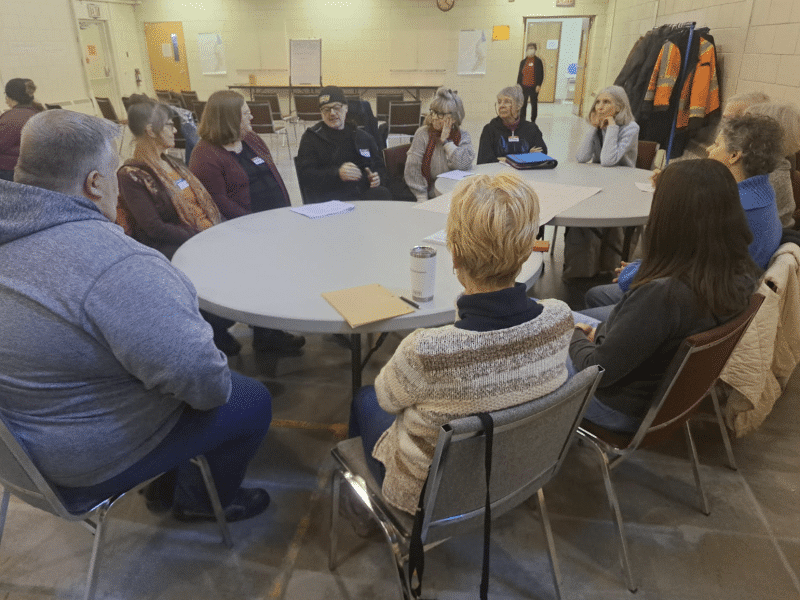

Students in a course currently offered at Trent University have some peers they might not have expected when they first enrolled as undergraduates. They’re sharing their classroom with over a dozen people aged 65 and up.

The course is a third-year psychology class focusing on the biology, psychology, and sociology of aging, according to Elizabeth Russell, who teaches it.

Russell has taught the course to young people for years, and she has documented how its curriculum helps students to understand older adults better and reduce ageist stereotypes.

But the professor has always had a hunch the course would be more impactful if it enabled students to develop relationships with older people themselves to see firsthand what it’s like to age.

So for this year’s class, Russell invited older adults to join the course as volunteers. Dozens of people aged 65 and up expressed interest, and 13 were selected. They don’t pay tuition, write exams, or get academic credit. But they attend lectures, ask questions, share their experiences and get to know the students in the class.

Russell said one of the goals is to find a “positive way to include older people in our classroom.”

And she said this pilot project is just the beginning of what she’d like to see happen at Trent. “I envision an intergenerational university where we … have older people on our campus all the time,” she said.

Halfway through the semester, some of the students are already reconsidering their assumptions about what it’s like to grow old.

Fourth-year psychology major David Glassman used to think of aging as a period of physical weakening and cognitive decline. Now, he thinks of it more as a period of “continual growth,” he said.

The average life expectancy in Canada is over 80 now, making our senior years “a big portion of life,” Glassman pointed out. “When I looked at that as a negative thing, it was kind of discouraging. So it’s really opened my eyes a lot to … the benefits of aging.”

Maeve Hartnett, also a fourth-year psychology major, said she’s learned from the class that “aging is a beautiful thing and it’s not something that people should fear.”

The course’s older volunteers are learning, too. Several said the experience has changed their perspectives on young people and given them more hope for the future.

“I find my attitude to young people is being modified,” said Diane King, one of the older volunteers. “You hear lots of rotten things about people between the ages of 18 and 25. And I find them a lot more positive, a lot smarter, and just nicer people than I expected.”

“I have a much more optimistic attitude about the future,” agreed fellow volunteer Gordon Campbell.

Volunteer Bill Bruesch said he signed up for the course because he thought it would be an “interesting experiment” that would lead to “better communication between pretty disparate groups.”

And so far, he’s liking it. “It’s fun. It’s interesting,” he said.

Canada is an aging country. People over the age of 65 currently account for about 19 percent of the population, according to Statistics Canada, and that proportion is expected to grow over the coming decades.

Ensuring a high quality of life for older Canadians begins with challenging the stereotypes often associated with aging, according to Russell.

“Modern research shows that [the] decline typically associated with aging is not inevitable,” the professor said. Instead, there are a variety of social and individual factors that contribute to how a person experiences aging, she added.

That means social supports for people of all ages will help to ensure Canadians stay healthy and happy as they grow older. “Supporting people who can be overlooked by society, during childhood and throughout their lives, can in turn enhance those people’s experiences of aging,” she said.

“Aging is joyful,” Russell said. “Aging is positive.”