Promoting preparedness in East City

A grassroots movement aims to help neighbours out in the next big storm

It’s freezing cold, on the second last Saturday in January, and Peterborough, still reeling from its third big blizzard in a month, is bracing for its fourth. People make their way in the back door of St Luke’s Anglican Church on Armour Road, and then down a somewhat convoluted series of staircases and hallways, to a big open space in the basement. It’s nearly 1pm.

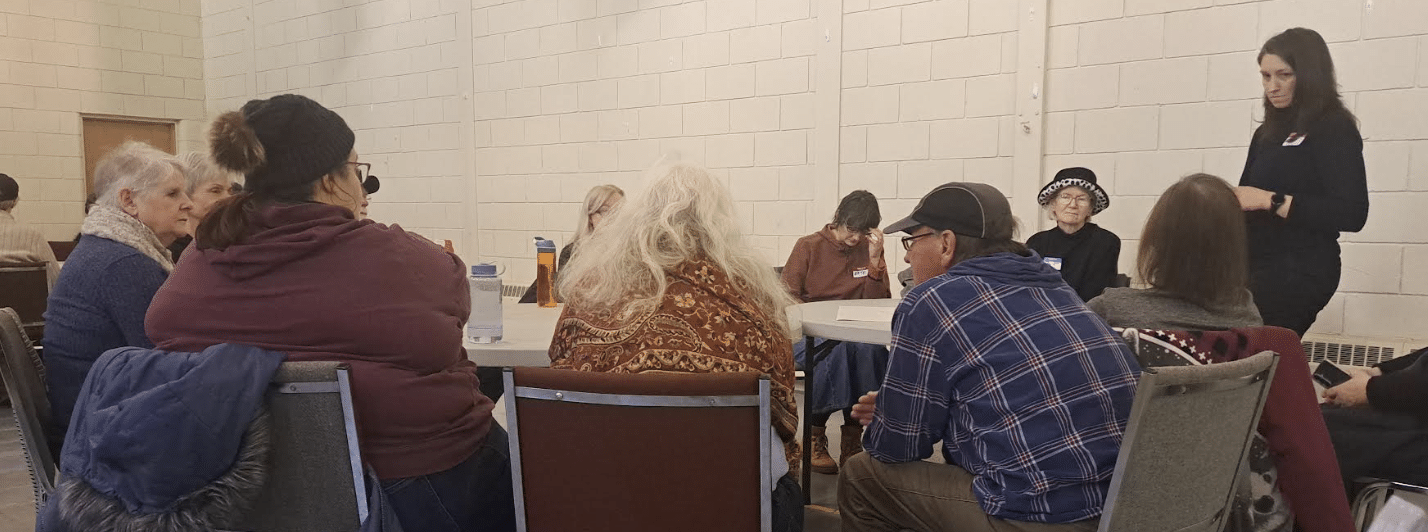

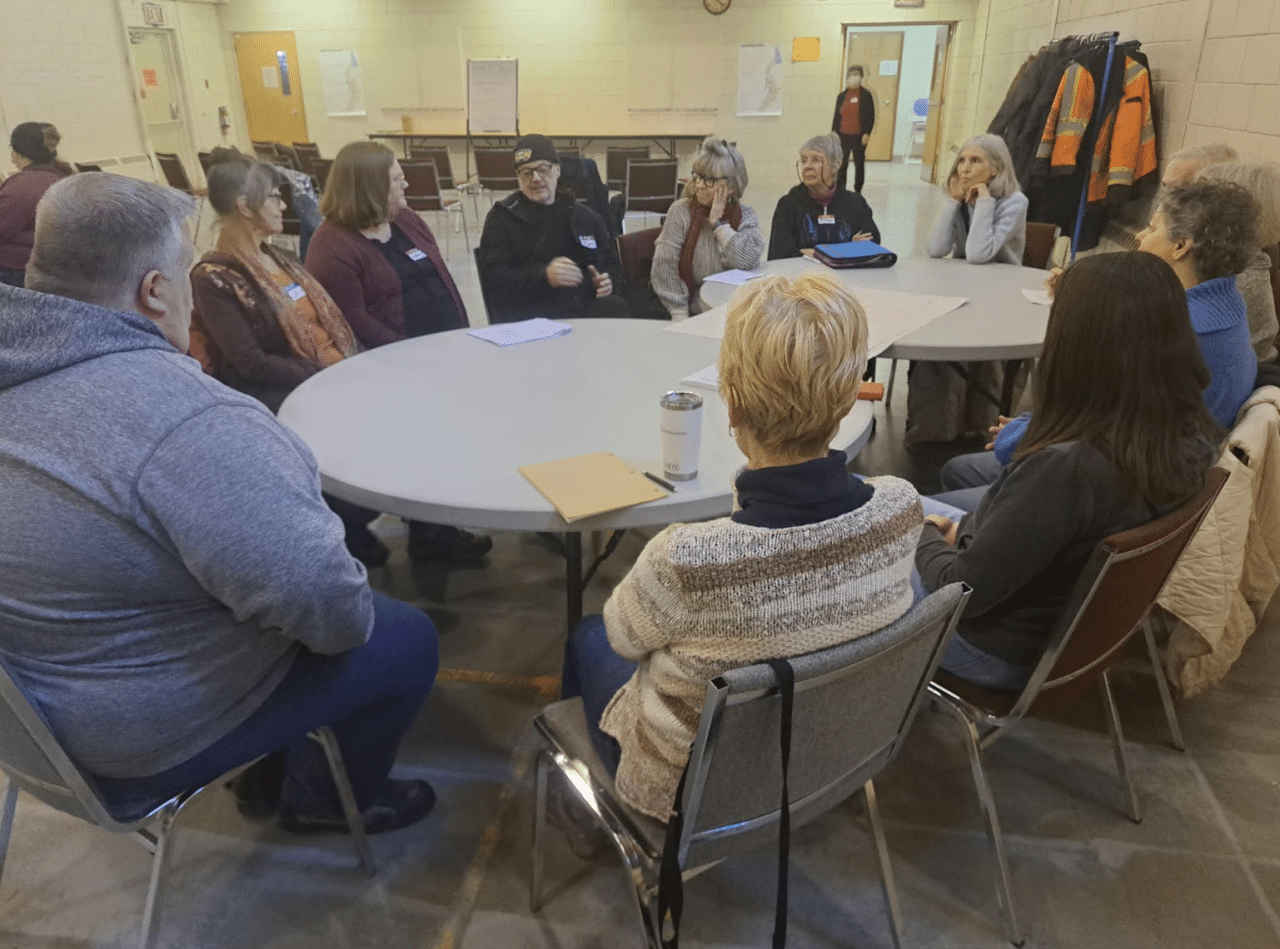

Inside the church basement, there’s a rectangular table with pitchers of water and stacked cups, and nametag stickers and markers; there are three circular tables spread around the room, surrounded by chairs. Other chairs are arrayed in three semi-circles in front of a flip board at the far end of the room.

This is the inaugural East City Emergency Preparedness Meeting, the first in a series of meetings to be held in the next few months. It is a grassroots, citizen-led local initiative, and part of a more widespread phenomenon globally as natural disasters become more commonplace.

Three organizers, Ashley Bonner, Mary Pickering, and Genevieve Ramage, open the meeting by presenting the results of a preparatory survey, shared on the East City Facebook page, asking people what they experienced in the March 2025 ice storm. It shows, among other things, that two-thirds of East City residents lost power for three days or more, and of those who lost power, more than three quarters lost home heating as well.

“The goal of the meeting was to create space for neighbours to start having vital conversations,” Bonner told Currents. “We realized how important it was for us to be connected as neighbours,” so that when the next storm comes, “we can respond instead of reacting,” and “ensure no neighbours are left behind.”

A history of disasters

Peterborough has had its share of disasters. Last winter ended with a massive ice storm that destroyed trees and knocked out power throughout the city. Three years ago, while we were still groggy from the COVID lockdown, a derecho, a hurricane-like windstorm, whirled through town, damaging buildings and knocking out power. Twenty years ago there was a major flood and a major electrical blackout back to back. We are very familiar with the unexpected.

Governments and the agencies they rely on to provide services struggle to meet our needs at the best of times, and several waves of austerity and downloading from the federal government to the provinces and from the provinces to municipalities have not made things any easier. Responding to crises when these brittle systems break down is a test of political competence that most jurisdictions fail at least somewhat.

Research suggests that citizen-led grassroots efforts can significantly improve outcomes, and that their impact is especially important when official responses fail.

An excellent example is the impact of Hurricane Katrina on New Orleans in 2005. Despite being a very predictable natural disaster, state preparation and response was half-hearted. For low-income residents, extremely threadbare systems broke down, with many of the most vulnerable people, notably Black people, left without official help.

This massive state failure inspired grassroots organizers to connect people to shelter and necessities, and ultimately to rebuild homes that had been destroyed. While it’s important to remember Katrina as a site of state ineffectiveness, and of environmental and administrative racism, the corollary is also key: citizens stepped up and helped each other survive.

It’s clear that, in a context of increasing environmental risk from climate change, cities must better allocate resources to being ready when the next predictable disaster comes.

The City’s recently released report about 2025 ice storm shows the scale of the work involved in responding, the many overtime hours the disaster required, and the compounding problems of having communications interrupted, and the clearing of obstructed streets delayed by downed but live hydro wires. It was a huge job, and conditions made responding very challenging.

There were several significant errors, though, one of which was the electrical company Hydro One erroneously directing residents to report power outages using the 911 emergency phone service. This could have been disastrous, if calls to report fire, medical emergencies, or violent crimes had been unable to get through.

No state system will ever be completely effective in a disaster. It is important to ask public authorities to do better, but getting through crises is a shared project, as previous disasters have shown.

Research also shows that shared memories of disasters and of neighbourhood response can be built on to increase response and improve survival, making it more likely that people with resources and skills already know the people who need help before the systems shut down.

Neighbours helping neighbours

Disasters don’t affect everyone equally. People have different needs and abilities. The philosophy at the root of these discussions is community solidarity across those differences: neighbours helping neighbours, rather than allowing inequalities of wealth and health determine who suffers the most in the next disaster.

A big part of preparation, and a key discussion point in the meeting, is identifying who needs help, and connecting them to people who can provide it.

“It’s an aging city, and people are more isolated,” Bonner says, and it’s important to “let people know they are not alone,” as “studies show the more people feel connected, the longer they can stay in their homes.”

A culture of preparedness is clearly multi-faceted. There are practical concerns – having power when the power grid fails, having heat when your furnace stops working – but more fundamentally it’s about relationships. It’s about preparing not ourselves but our communities, to be resilient in a disaster.