Al’s Pizza and Yee’s Chinese Food is a legendary late-night food spot. For owner Chris Ho, it’s a living.

The beloved restaurant carries on a local Chinese food legacy that dates to the 1930s

On a hot evening this spring, I roll up to the corner of Water Street and Parkhill Road to meet my friend Mikey. We are there to eat a Peterborough delicacy Mikey introduced me to almost twenty years ago, the pizza roll from Al’s Pizza and Yee’s Chinese Food.

The pizza roll is simple: a large egg roll pastry, filled with pizza toppings instead of the usual egg roll fillings. It’s an unlikely fusion of the restaurant’s two distinct Italian-Canadian and Chinese-Canadian menus. Over the years, the pizza roll has become an underground favourite in Peterborough’s culinary culture, gaining fans among many successive generations of students and late-night bar-goers.

Al’s Pizza and Yee’s Chinese Food is an oddity itself; a late-night hole-in-the-wall with the distinction of being two restaurants in one kitchen. The business occupies a brick house with two signs out front. On the north façade, bright blue capital letters advertise Al’s Pizza. But on the west facing wall, an illuminated sign invites you to Yee’s Chinese Food. Only the Yee’s sign has a phone number — but don’t bother calling, it doesn’t reach the restaurant.

Inside is no less eccentric, with old panelling, artificial flowers, and Christmas decorations that have weathered many summer evenings. The menu is handwritten on brightly coloured Bristol board with sharpie marker. Corrections and amendments are ample and evident. Small figurines and knick knacks perch on the counters and sills. Handwritten motivational messages encouraging patrons to “Exercise” and “Eat Well” hang from above.

This is the place I know as Al-Yee’s. It’s been here for over 30 years.

Mikey grabs our order and catches up with Chris Ho, the owner of the restaurant. Ho is slight, with bright brown eyes, a quick smile, and an easy way about him. His grey moustache is the only thing that might betray he’s in his early 60s. He hasn’t seen Mikey in years, but he still remembers him and is glad to hear he’s back in town.

We take our paper bags across the road to Inverlea Park, where Mikey reminds me that there is a method to eating a pizza roll. He pushes the paper bag down to expose the top of the roll. Mikey bites the top corner off the roll the way I might snip the corner off a bag of milk, then carefully tips it, pouring out a little stream of sizzling fryer fat onto the dirt in front of us. This step, Mikey assures me, is essential if I want to avoid burning my mouth.

Having followed Mikey’s lead, I am cleared to dig in. The first bite is hot, greasy, and delightful. I always forget how delicious fryer food can be when it’s fresh. The egg roll pastry is crunchy, flaky, and golden. The whole surface of the roll is covered with tiny air bubbles. The filling is classic pepperoni and cheese, slick with an herby oil and a sweet tomato sauce that spills onto my shirt almost immediately.

Ho is pretty sure he invented the pizza roll. At least, he says, he had never seen it done before he started making them in the mid-nineties. The dish was devised as a sort of gateway food to introduce Ho’s pizza-loving customers to the restaurant’s Chinese menu. It was 1993, and 241 Pizza had just opened across the street. Al’s Pizza couldn’t compete with the chain’s prices, and Ho started to notice a drop in business. “We had to diversify to survive from the competition,” he says.

Ho’s invention worked. He tells me customers would try the pizza rolls and then feel braver about ordering the egg rolls, chicken balls, and other Chinese-Canadian dishes on the Yee’s side of the menu board. Now, he says, Chinese food makes up the bulk of his business.

But how did Ho come to run two restaurants under one roof — each with a distinct menu and sign out front? And if Ho’s first name is Chris … who is Al? And who is Yee?

I sit down with Ho in the restaurant’s small dining room around midnight one Wednesday to get the story. Ho smiles under his mask, and assures me I’m not the first one to call him Al. And the reason he runs two restaurants with two namesakes is actually pretty simple. First, he bought a pizza business from a man named Al. A few months later, he bought a Chinese food business from a family named Yee.

The real Al, Ho tells me, opened the pizza shop on Parkhill Road in the 80s but later decided to sell it when he needed some cash. The timing was right for Ho, so he bought the business in 1990.

It wasn’t a career path he was necessarily planning for himself. Ho tells me he moved to Canada from Hong Kong when he was young. He went on to get a diploma in business administration from Fleming College and then one in computer science from Loyalist College. After that, he was a software salesman for Nortel in the 80s. But he didn’t like that job — it required too much travelling, for one thing.

By 1990, Ho was married. He wanted to settle down and raise kids, and he needed a livelihood he could depend on. “For an immigrant in the job market, it’s hard to compete with locals,” Ho says. By opening his own restaurant, he could make a living for himself. “Chinese food,” Ho says, pausing. “It’s easy.”

I ask Ho when he expanded the original Al’s Pizza menu to include Chinese food. That happened quickly, he explains. He did it a little later in 1990 to save the legacy of the Yee family, who had served Chinese food in Peterborough since the 1930s.

Like many Canadian towns, Peterborough has a long history of Chinese restaurateurs. Between 1906 and 1951, Chinese residents of Peterborough opened no less than 13 restaurants. By the 1920s, Peterborough had an estimated 40 Chinese immigrants living in the city, most of whom worked in restaurants, laundries, and grocery stores — the industries considered acceptable for Chinese people in Canada, who faced racism and exclusion in their adopted home.

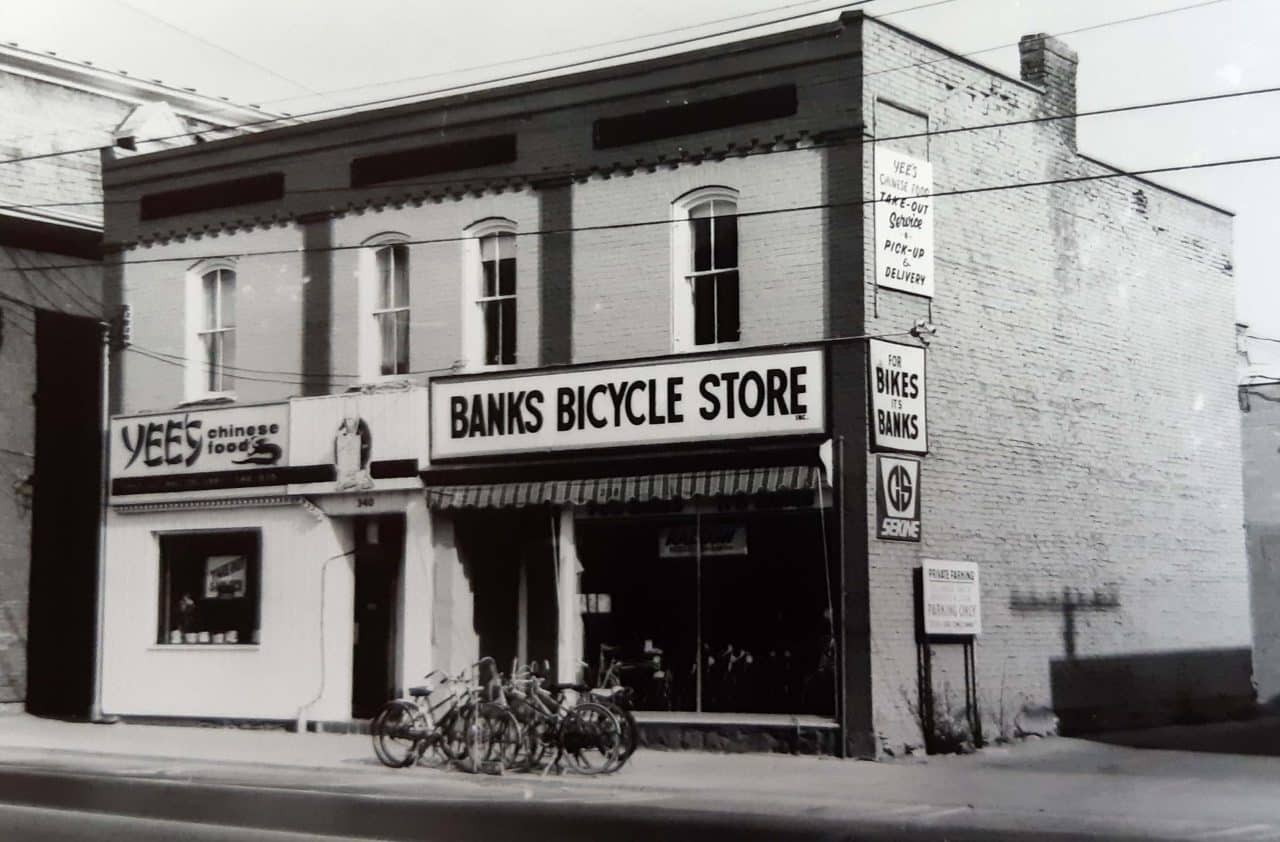

According to reporting in the Peterborough Examiner, Shung Yee immigrated to Canada and opened the Hollywood Cafe on Charlotte Street in the 1930s. In 1951, Shung Yee’s teenage son Len Yee moved to Canada and began working in the restaurant, eventually becoming its manager. But the Hollywood Cafe closed in the mid-60s, and Len Yee moved to Quebec for a few years. He returned to Peterborough and opened Yee’s Chinese Food, a take-out spot, with his wife Helen in 1970. “Ours was the first Chinese food business to open a take-out service in Peterborough,” Len Yee told the Examiner.

The family operated Yee’s Chinese Food out of its Aylmer Street location for two decades. The Examiner reported that Len Yee was “proud of his unique dishes, particularly his special chicken roll, nuts and vegetables rolled in chicken, deep fried and served with vegetables.”

By 1990, the Yees were ready to move on. “They were looking to retire,” Ho explains. “They were selling it quickly. So, I bought the restaurant equipment, the sign, everything.”

The sign was moved from Aylmer Street to Parkhill Road and installed on the west-facing façade of Ho’s business, right beside the Al’s Pizza sign. “I didn’t change the sign,” Ho says with a shrug. “Why would I?”

Ho already knew the ins and outs of Chinese-Canadian cuisine. He’d learned it on the job, memorizing recipes for chop suey and sweet and sour sauce in the kitchen of a different Chinese restaurant during his studies at Fleming College. He worked late in those days, sometimes past midnight, before rising at 7:00 am to get to his business classes. So taking over Yee’s came easily to him.

Ho gets up to serve a customer who has just walked in, a big redheaded man who appears to be in his late thirties. It’s clear that the two men know each other, and Ho inquires after the man’s wife and children, how are they doing and is the youngest one feeling any better? They keep chatting even as the man pays for his order and makes his way out the door with two large paper bags in his arms, just barely starting to spot with grease. When Ho returns to my table, I ask him if he has ever felt isolated in Peterborough.

“Not really,” he says with a shake of his head. “I make friends as I go. It comes naturally to me. People treat you the way you treat them. So I talk to them. I smile.”

Ho tells me that the customer who just came in has been a regular for almost twenty years. Most of his customers are long-time regulars, he says, and he gestures toward the snapshots on the walls of glassy-eyed Trent students and families celebrating birthdays.

“I listen to the people, and they open up to me,” Ho says. When a customer shares troubles or worries with Ho, he waits until the right moment and then tries to offer some advice. Sometimes, the customer comes back for more conversations.

While Ho assures me that he never had any difficulties with locals, he laughs when he tells me his mother used to ask what the hell he was doing running a Chinese restaurant with an education in computer science and business administration.

“I’m independent. I’m self-sustaining,” Ho answers. “I am able to support me and my wife and my two kids. That’s everybody’s goal.”

He speaks with a frank practicality about his business. The restaurant allowed him to be financially independent, and wasn’t that why his mother had wanted him to be in Canada in the first place? “I don’t ask for too much,” he says. “I’ve got a restaurant, a house, a roof over my head.”

Ho did what he had to do, in other words. He paid off the building’s mortgage in 2015. He takes Tuesdays off now. His boys are all grown up. One is a mechanic.

It’s past midnight now, and the restaurant is getting busier. The telephone is starting to ring with orders for delivery and pick up. I notice a wooden dinosaur skeleton with Christmas tinsel draped over its horns. Ho says his son made it when he was small. Ho likes decorating the restaurant, so that people can see the place has a soul.

Ho walks behind the counter to check the order chits and get back to work. “You don’t have to be a rich man to be happy,” he says thoughtfully, “but you need a full tummy to be happy.”

Photos by Will Pearson unless otherwise noted.