Uncovering the history of the Curve Lake Day School

New book reveals a pattern of abuse, cultural erasure, and systemic neglect by the Canadian government

On her first day of school, Valorie (Val) Whetung was “terrified. I was a wimp.” Born in 1948, she was one of five siblings who attended the Curve Lake Day School, which was operated at the time by the United Church and overseen by the Department of Indian Affairs. “We had this teacher in grade one… that’s how I knew that we didn’t get good teachers, because all she wanted to do was save the savages. And so, she spent most of the day telling us about heaven and hell.”

The school paired religious indoctrination with a basic education in “the three Rs” (reading, writing, arithmetic), strictly in English and not in Anishinaabemowin, and often backed up by the threat of physical violence. “We were like little robot kids,” said Whetung. “We would never step out of line. And they had straps. They all had straps.”

The Curve Lake Day School operated at Curve Lake First Nation from the 1860s until 1978, overseen by the Department of Indian Affairs and administered by a series of religious institutions, including the Methodist Missionary Society and the United Church.

Much of the focus of discussion of Canada’s history of Indigenous education, including work by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), has focused on the horrors of the residential schooling system. However, there were also 699 day schools across Canada, and new research is showing that they too played a significant role in the indoctrination and subjugation of Indigenous Peoples.

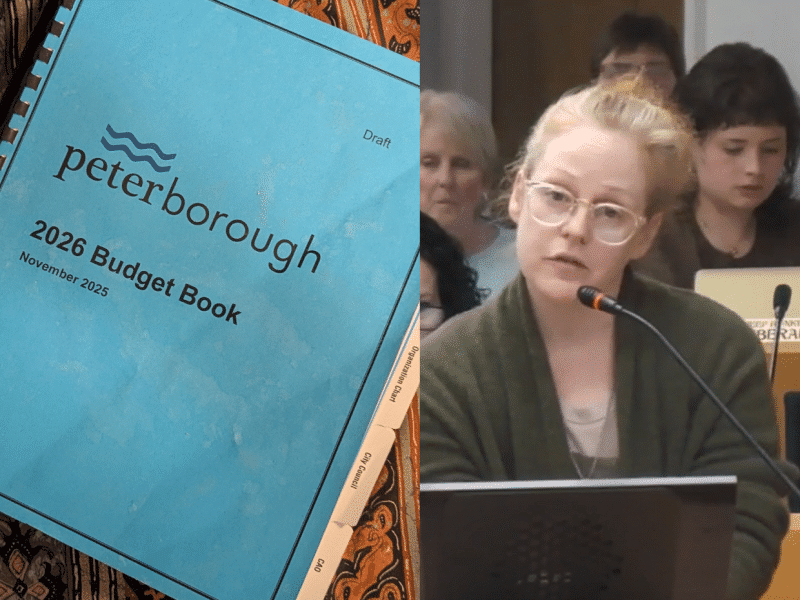

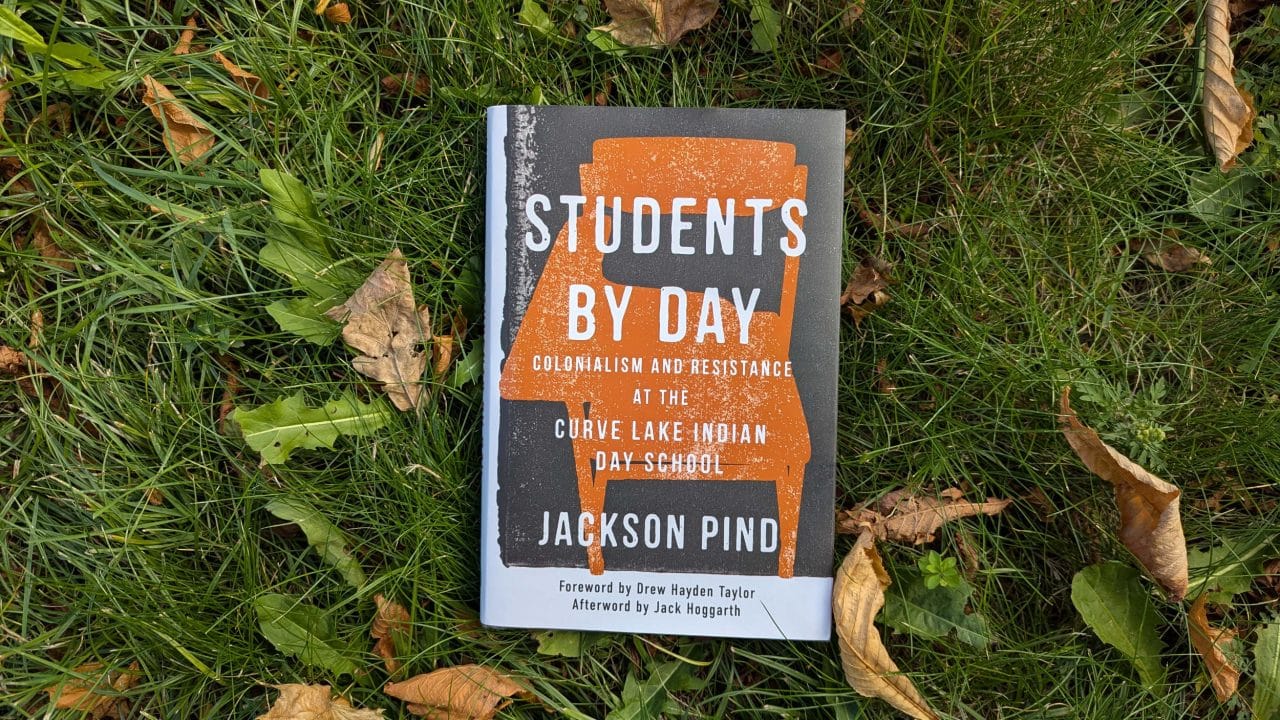

Jackson Pind’s new book, Students by Day: Colonialism and Resistance at the Curve Lake Indian Day School, documents the abuse of students, including Whetung’s story, but also a shows a wider pattern of neglect and underfunding by the colonial administrators, clear and direct evidence of the systemic neglect of Indigenous communities by a federal government who claimed to be their caretakers.

Approaching the community with care

Now an assistant professor at the Chanie Wenjack School for Indigenous Studies at Trent University, Pind’s personal history is closely tied to the region, which helped him approach this difficult topic with local knowledge and cultural sensitivity. Pind grew up in the Peterborough (Nogojiwanong) area and spent a significant part of his childhood around Curve Lake. His mother’s family comes from Alderville First Nation and were enfranchised in 1910, and he also has familial connections to Curve Lake First Nation.

Pind tells Currents he was studying education at Laurentian University when the TRC report was released in 2015. “It started me on this whole research journey to connect back to my Indigenous ancestry, but also to learn more about the history of education at large.” Eventually, guided by Raymond Mason, an Elder and survivor of the residential and day school systems, Pind decided to focus on the under-told story of the day school system, and to return to his home community to do it.

Pind’s approach to Curve Lake First Nation was informed by an awareness of the history of academic exploitation of Indigenous communities, which has included theft of Indigenous cultural objects, knowledge, and even blood. He was guided by modern research principles of “data sovereignty,” which considers issues of “ownership, control, access, and possession” over research findings, known collectively as OCAP.

“If you read through any of the archives for day schools,” says Pind, “you quickly realize that this is very personal information. It includes people’s names, it includes difficult histories about people’s families and challenges that they had. In order to look at that information, you really should have the permission of the First Nation, and then also do your best to make sure that that information is then held in that community going forward.”

There was also a tangible benefit to returning this information to the community: the Indian Day School Settlement Agreement was completed in 2019, and for survivors to be eligible for the maximum compensation, they have to show documented evidence of their histories in the school. As TRC chair Murray Sinclair noted, survivors “have to find the documents; they have to prove they went to the school; they have to match the records that the department provides to the law firm… And we’re talking about a population of people whose literacy rates are the lowest in Canada.”

This was all part of Pind’s pitch when he approached Curve Lake Chief Emily Whetung (then later Chief Keith Knott, following his election), the Band Council, and then the community as a whole.

Pind’s archival research included over 10,000 pages of documents about the Curve Lake Day School, held at the Library and Archives of Canada, which he digitized, read through, and eventually provided to the community for their own use. Later, Pind returned to the community to ask permission again, to conduct in-person interviews with five survivors about their experiences.

A history of neglect and abuse, but also resilience

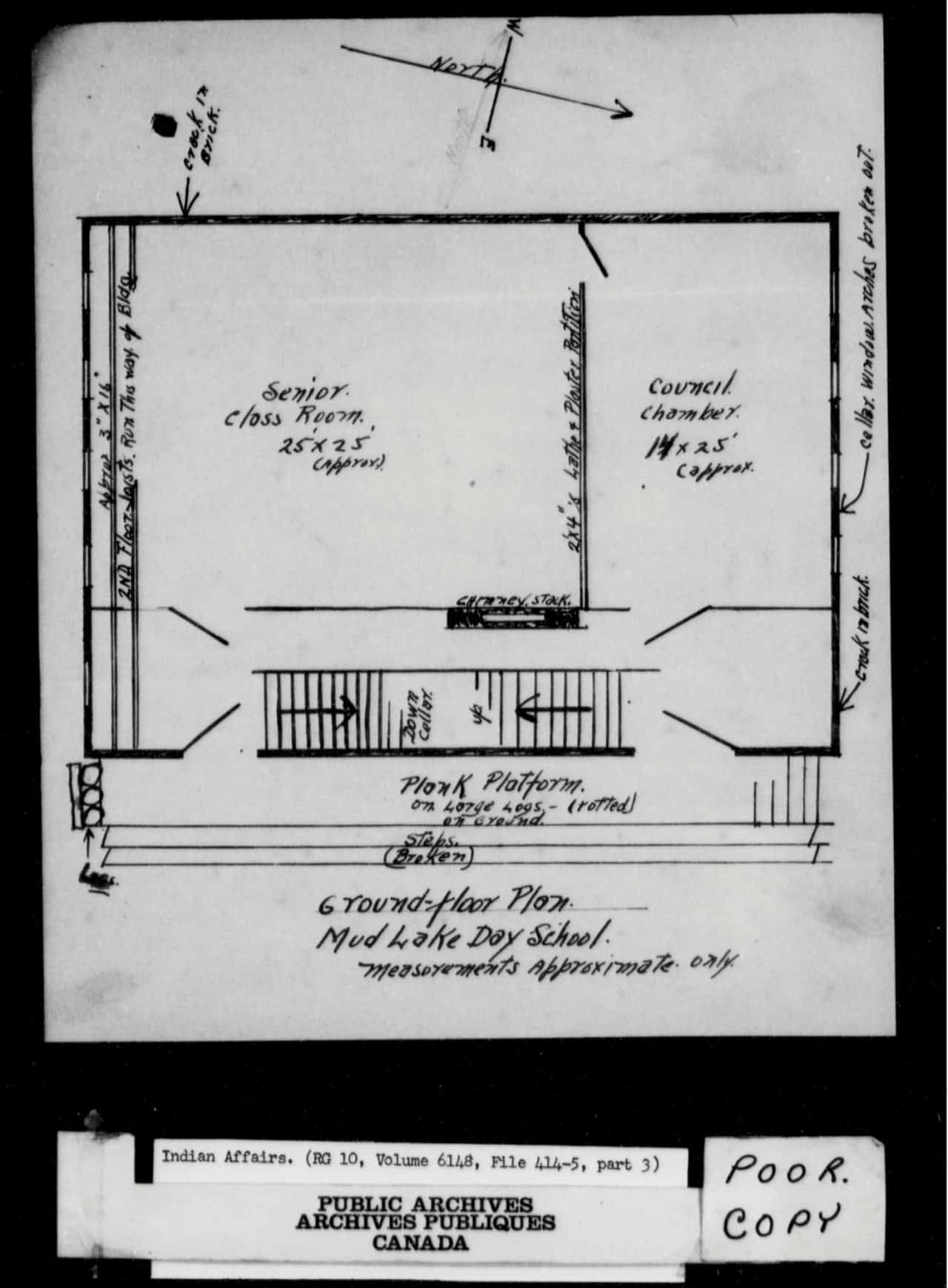

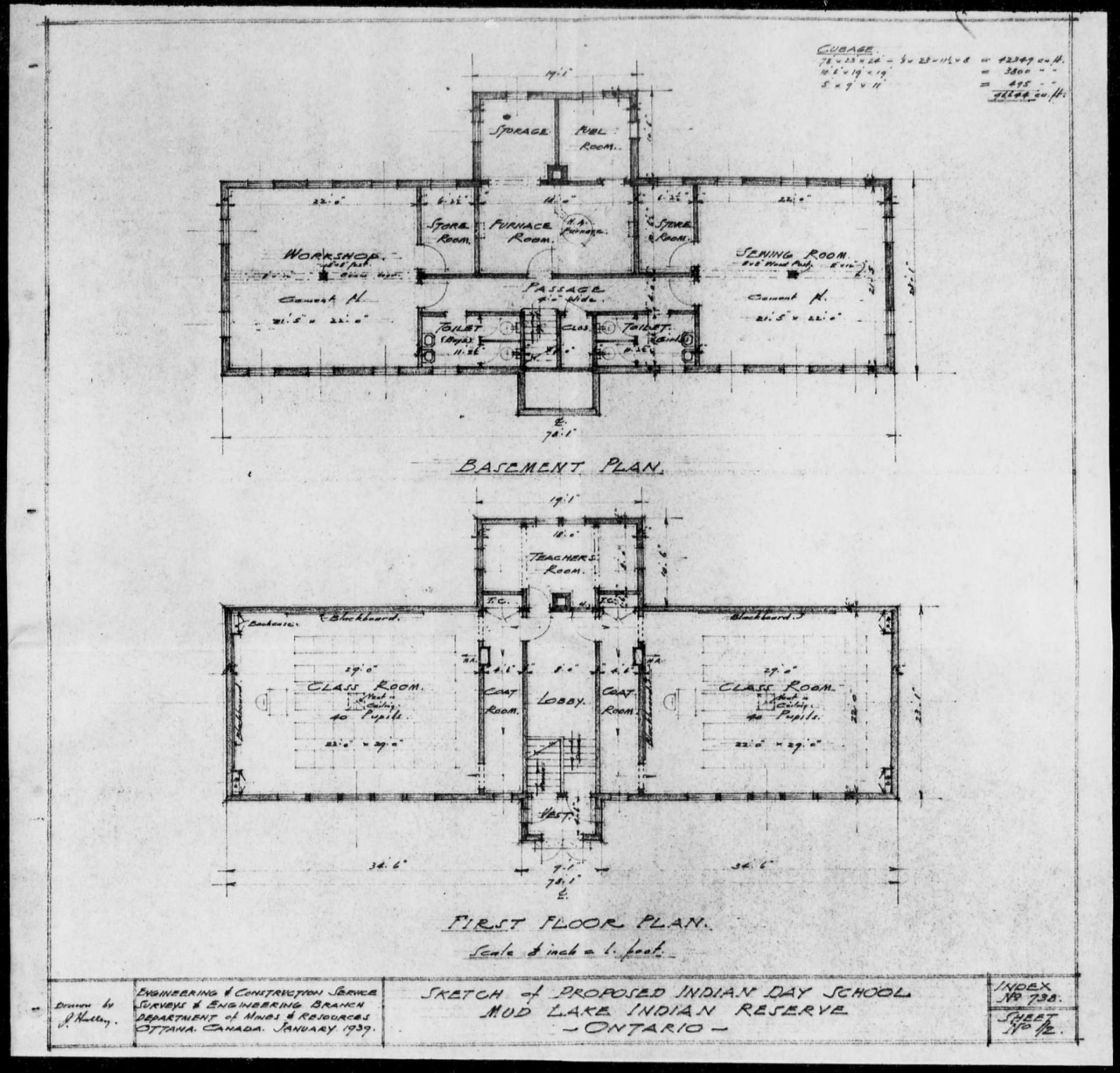

The first portion of Students by Day, taking place too long ago for any survivors to remain, is based in large part on a review of archival documents: accounting ledgers, inspection reports, architectural diagrams, letters, and so on. Together, they paint a frustrating portrait of never-ending bureaucratic disorganization, with frequent conflicts between the Band Council, the Indian Agent, the church administrators, and the Department of Indian Affairs.

Pind quotes multiple requests by the Council and Chief for improvements to the school facility (or even just for a qualified teacher to be hired), which are repeatedly denied, ignored, or undermined by contradictory statements by the local Indian Agent.

At the time, Council funds were held “in trust” by the Canadian government, meaning the Council had to ask permission for even basic amenities, like a ladder to help children escape the second floor of the schoolhouse in case of fire, or money to take out an ad in the Peterborough Examiner to advertise for a new teacher. Notably, the latter request was repeatedly denied over the course of multiple decades, as the colonial administrators hired a procession of underqualified educators, few of whom lasted more than a few years and which included, as Pind colourfully describes, “circus trainers… misogynists… and draft dodgers… indeed, the Department sometimes found it preferable to provide no teacher at all.”

The schoolhouse itself was also a perpetual problem, housed for several decades in the rapidly aging and overstuffed council hall, even as the population of students more than doubled (see above image). Requests for funding (or even just requests for the Council to use its own money) were repeatedly denied, and when permission was finally given to build the new schoolhouse (see below image), there was pressure to secure the lowest price possible, resulting in shoddy workmanship and further letters requesting essential fixes.

At every point, Pind draws a connection between specific incidents and the wider systemic issues they represent: “By constantly undermining Council and stealing funds from the community, the government and church maintained the status quo, and they did so at a massive cost to Indigenous students.”

As the timeline in the book progresses, it adds more first-hand accounts from survivors. They tell of abuse, neglect, and cultural erasure, but their stories also document the slow path towards increased self-determination.

Elsie Knott attended the Curve Lake Day School in the 1930s. “When she arrived in school, she found that her language had been banned, and the names of students who were ‘caught talking Indian’ … were listed on the blackboard with big Xs beside them.” The school, which was primarily set up to prepare students to work in the trades, offered no education beyond Grade 8, and the the closest high school was 24 kilometres away in Lakefield. For an Indigenous woman like Knott, there was no expectation she would continue schooling.

She carried that experience forward into 1954, when she became the first female Chief of a Band Council ever elected in Canada. Under her leadership, Curve Lake began offering special programs at the day school teaching Anishinaabe language and culture to young children and expanding art education. While Chief, Knott also took out a loan to purchase a hearse and convert it into a makeshift bus to take students to Lakefield for high school. The Knott Bus Company soon expanded, with two 28-passenger school buses ferrying interested students of all genders from Curve Lake to Lakefield for high school.

Meanwhile, Curve Lake also became one of the first reserves in the country to take over their own administration from the Department of Indian Affairs. A locally appointed band administrator was put in charge of the community’s finances, overseen by Council. In the fist 15 years of this new system, “the community created over 100 homes, established a sewer system, paved roads, and enabled cable and telephone connections.”

The Curve Lake Day School was officially closed in 1978, with the community taking charge of their own daycare and K-3 school, the Curve Lake First Nation School, which remains to this day.

“We need truth before reconciliation”

In modern narratives, including what was presented in front of the TRC, the story of Indigenous education has been dominated by residential schools, with day schools somewhat forgotten. Currents asked Pind about why this might be the case.

“I think in some ways it was a strategic decision to focus on just this one issue that people could understand,” he said. “They were taken far from their homes, abused, died at school, and we need to reconcile with that; whereas in some ways, the day school is what students still experience today.”

Funding has improved for schooling in First Nations, and the communities have much more authority and autonomy in determining their own education, but it remains a system with significant funding and infrastructure challenges, resulting in overall poorer educational outcomes for Indigenous students.

Among the 94 Calls to Action that came out of the TRC, Call #9 was for the federal government to create an annual national report comparing educational spending and outcomes for Indigenous and non-Indigenous children – another piece of data that would be useful for Indigenous communities and the government at large. According to non-profit group Indigenous Watchdog, ten years after the TRC report, 80 out of the 94 Calls to Action remain unfulfilled, and Call #9 is among them.

Last month, on National Day for Truth & Reconciliation, Pind returned to Curve Lake one last time, to provide a final overview of the book and distribute 50 copies to the community. It was the end of his research commitment, but Pind says there’s much more work to be done. There are still millions of pages of documents at the Library and Archives of Canada, relating to the other 698 day schools across Canada.

Says Pind near the end of Students by Day, “We need truth before reconciliation.”